The Inequality Wars and the concerning state of academia

What the Inequality Wars are all about, and how it reflects structural problems of academia

Over the past few months, I’ve mainly written about geospatial topics. However, I haven’t had a chance to discuss the other topic I work on—economics.

So today I wanted to change things up by discussing a recent debate in economics over the issue of inequality. This debate is all about the question of how bad inequality is.

And while this debate is important in its own right, it actually touches on a number of wider issues:

the role of data and ideology in research, and

the incentive structure of academia.

These broader issues aren’t examined as much as they should be. So I’m hoping to change that here.

Context

The ‘Inequality War’ is essentially a debate between two teams of academics.

On one team are the French economists: Thomas Piketty (whose tome, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, was released in 2013), Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez.

On the other team are two American economists, Gerald Auten and David Splinter. They published a study in 2024, looking at inequality in the US.

The point of contention between these two teams is that they come up with two very different stories around inequality. And they do this using the same underlying datasets.

They both examine the income of the top 1% of earners in the US and determine their portion of the country's total income (total income refers to all the money earned by US residents in a year).

The basic idea is that if the richest people in a country (i.e. the top 1% of earners) earn a larger portion of a country’s overall income, then that country has a pretty big issue with inequality.

Piketty et al. found:

the top 1% earned 9.1% of national income in 1961,

this grew to 15.1% in 2019.

Auten and Splinter, on the other hand, find that:

the top 1% earned 8.1% in 1960 and

this only grew slightly to 8.8% in 2019

So what’s going on here?

How can these two teams come up with wildly different results using the same data?

To answer this question, it’s worth (briefly) revisiting the work of Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Why Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century was Groundbreaking

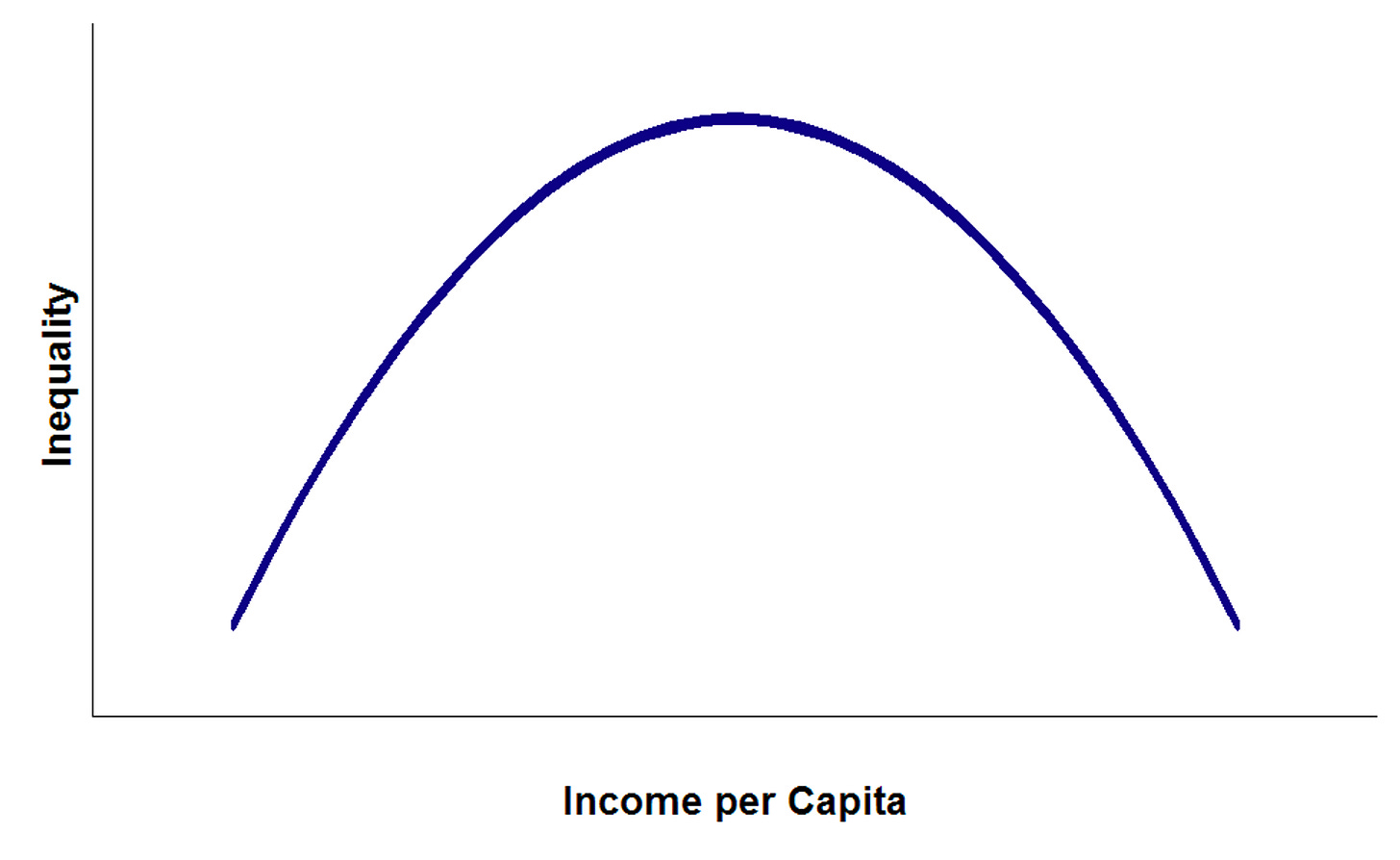

Prior to Piketty’s work, the most mainstream understanding of inequality could be summed up by this curve:

This curve, known as the Kuznets Curve, was proposed by the American economist, Simon Kuznets. According to this, as an economy developed (and income per capita grew), inequality would first increase, before steadily decreasing.

Kuznets wasn’t just waving his hands and coming up with a theory on inequality.

Instead, he was empirical.

He based his theories on thirty-five years of data for the US (from 1913-1948). This data came from:

US federal income tax documents, and

His own estimates of US national income.

After studying the data, he came up with a few theses around inequality:

Early Development: Initially, as countries develop, the rich find more investment opportunities, while an abundance of workers keeps wages low, increasing inequality.

Mature Economies: Later, the focus shifts towards investing in education and skills. Inequality might hinder growth by limiting poor people's access to education.

Industrialisation and Urbanisation: With industrialisation, people move from rural areas to cities for better jobs, creating a gap between rural and urban incomes. However, as average income increases, democratisation and social welfare help distribute the benefits of growth more evenly, reducing inequality.

Taken at its extreme, Kuznet’s theory has been interpreted by some as follows:

income inequality will inevitably decrease in advanced phases of economic development. As a result, if we’re simply patient, economic growth will ultimately benefit everyone.

Piketty, however, became frustrated that over the decades since Kuznets, there hadn’t been a big effort by economists to collect historical data on inequality.

Instead, economics just continued to produce lots of broad theories about inequality, which weren’t grounded in facts or data. These studies would broadly align with Kuznet’s theorisations that inequality inevitably accompanies economic development, but that it ultimately fades away.

As a result, Piketty famously declared in the introduction to Capital in the Twenty-First Century that:

“the discipline of economics has yet to get over its childish passion for mathematics and for purely theoretical and often highly ideological speculation, at the expense of historical research“.

Piketty and his collaborators wanted to study the dynamics of inequality by looking at a lot of historical data. They did this by building long time series of data on income and capital for countries like the US, France, Germany, and the UK.

Whereas Kuznets only studied 35 years of data for the US, Piketty was able to study over a hundred years of data for a handful of countries.

Piketty’s findings: capital and income

Based on Piketty’s data crunching, he produced several key findings.

The most important finding relates to the capital/income ratio. Piketty finds that this ratio is one of the biggest factors explaining inequality.

Let me explain.

When the return on capital is more than the economy's growth rate, it leads to increasing inequality.

This happens because people who own capital (e.g. real estate, stocks, etc.) see their wealth grow faster than the overall economy. Meanwhile, people who mainly rely on labour (i.e. salaries) for wealth find it harder to keep up, as wages tend to grow slower than returns on capital.

However, Piketty also examines some of the drivers of income inequality (i.e. in addition to looking at the differences between those who earn money from income vs capital). These drivers of income inequality are particularly important in the US.

He finds:

Education-income gap: the wage gap between college graduates and those who don’t go to university has increased.

The ‘super-manager’: since the 1970s, senior managers of companies have seen their incomes growing a lot quicker than other employees. This is far more pronounced in the US than in European countries.

Taken together, this means that the top income earners are accruing more than other income earners.

Auten and Splinter’s Findings: income inequality

Earlier this year, Gerald Auten and David Splinter published a paper in the prestigious economics journal, the Journal of Political Economy.

They argued that there were several issues with how Piketty and co. compiled their income data in the US.

Initially, in 2003, Piketty and Saez started using IRS data from the US to study income inequality. It was groundbreaking work because it used tax data, which was more reliable than other studies that had simply surveyed people on their incomes.

However, there’s one major issue with tax data: it isn’t comprehensive — it doesn’t capture all forms of income.

Piketty, Saez and Zucman attempted to address some of these limitations and create a more complete dataset. But, to do so, they had to make a number of assumptions.

These related to:

Pre-tax income:

Under-reported income: how much income the wealthy don’t report - e.g. due to using tax havens)

Retirement income: do you exclude ‘rollovers’ (i.e. moving retirement savings from one fund to another)

Other taxes: e.g. how to deal with property deductions, social insurance benefits, corporate income, etc.

After-tax income:

Government Consumption and Transfers: These include social transfers, like social security, which can differ in how they're allocated to individuals.

Estate Tax and Corporate Taxes: e.g. adjustments based on how these taxes are distributed across different income earners.

The bottom line is that changing some of these assumptions led Auten and Splinter to reach very different results to Piketty and co.

Let’s run through the main two assumptions:

Tax evasion: Piketty assumes the top earners have the same proportion of unreported income as they do reported income. In other words, they’re arguing that, due to tax evasion, rich people have just as much unreported income as reported income. This is a lot. Auten and Splinter, however, use IRS audit data to estimate unreported income, which allocates much less to top earners.

Retirement income: Piketty and his team believe that the top 1% receive a larger share of retirement income. However, Auten and Splinter argue that most of these funds are simply people moving their retirement savings from one fund to another. It’s not them receiving more income.

The full differences are laid out in Table 4 of Auten and Splinter’s paper:

However, as a result of these differences in assumptions, we end up with massively different measures of inequality, as summed up in these graphs:

What are the outcomes of this debate?

There are three possible outcomes I see from this debate:

People get distrustful of the data

We try and find a compromise between the two studies

The patient (and painful) path

Let’s examine each of these:

1. Ideology and distrust in the data

After Auten and Splinter’s paper was published, Piketty launched a scathing response on X, calling Auten and Splinter ‘inequality deniers’:

He then declared that “inequality denial is as dangerous as climate denial”:

This is a wildly ideological move.

It was particularly surprising for someone who had lamented the ideological nature of economics, and who previously criticised economics for being too ideological and not focused enough on empirical, data-driven research:

“The discipline of economics has yet to get over its childish passion for mathematics and for purely theoretical and often highly ideological speculation, at the expense of historical research and collaboration with the other social sciences” — Piketty, Capital in the Twenty First Century

The bigger issue though is that Piketty's reaction could lead to public skepticism about economic data.

People might start choosing teams—either team “Inequality Accepter” or team “Inequality Denier”—based solely on personal beliefs instead of what the data shows.

This is a classic example of how an academic disagreement can devolve into a political issue, with people aligning with one perspective over another due to ‘beliefs’, instead of trying to get to the bottom of what the evidence actually says.

On the one hand, I get it.

It’s much easier to just pick a side based on personal beliefs than it is to revisit all of the individual assumptions that were used in constructing a database on income in the US. But that, unfortunately, means choosing the easy option over the scientific method.

And that, history has taught us, can lead to some pretty disastrous outcomes.

2. Finding a compromise

Some people have argued that the truth of inequality probably lies somewhere in-between the estimates from Piketty, and Auten-Splinter.

The idea then is to view Piketty and co’s data as the ‘upper bound’ and Auten and Splinter as the ‘lower bound’ on inequality.

However, I find this quite unhelpful because the estimates are vastly different. There’s a 6% difference between the two estimates — this is huge:

It’s the equivalent of saying, “we’re pretty confident that inequality has either not increased, or has increased quite a bit”. This isn’t really telling us much.

So what’s a better approach?

3. The patient (and painful) path

The alternative approach is what I call the ‘patient and painful path’.

It’s pretty much how research unfolds, and unfortunately, this doesn’t give us the quick answers we crave.

This path starts with a new theory being thrown into the mix.

These theories are then either supported by new evidence or challenged (and subsequently refined) by it. This is a slow process. But it's how we inch closer to understanding complex issues.

So this is where we’re at now with the inequality debate.

Piketty’s ideas were introduced. Some of the core assumptions (for the US) have now been challenged. And we’re waiting for a consensus to emerge.

Piketty, Saez and Zucman have issued their own in-depth commentary on the topic, while Brookings has also waded into the conversation.

But so far, a consensus about the degree of inequality hasn’t yet emerged. However, it’s just a matter of time.

How these debates turn ideological: the incentive structure of academia

I realise it’s pretty anticlimactic to say “We need to wait to work out the true extent of inequality in the US”.

But, I actually think there’s a much deeper and more interesting dimension to this debate. It’s about the question of how these economic discussions turn into ideological battles.

We often hear the term ‘polarisation’ being thrown around. Many topics are becoming ‘polarised’, such as concerns over race, gender and sexuality theories that have ultimately led to thousands of books being banned in the US.

And ‘polarisation’ is just another way of saying that deep ideological battles are taking place and becoming more severe.

So how then can these types of ideological debates emerge—particularly in the academic space?

Reason 1: The academic incentive structure

It’s important to understand that while academia incentivises publishing high-quality research, that’s not the full story.

First, let’s examine what’s required to publish high-quality research.

It’s a combination of factors:

Publishing something rigorous

Publishing something that’s novel/different

Publishing something that’ll be cited a lot

In most cases, publishing in the top journals in any field requires high-quality work. For the top economics journals, oftentimes a paper takes about 3-5 years from initial work to ultimate publication. Numerous robustness tests are done, and several rounds of reviews are undertaken.

However, the novelty factor is huge. You either want to produce an analysis with:

a novel dataset (e.g. the first use of nightlights),

a novel method (e.g. a new ‘natural experiment’, or even a new methodology (e.g. the new ‘synthetic control’ method)

or a surprising result (e.g. something that challenges ‘common wisdom’)

Academics are therefore incentivised to come up with novel (or surprising results). This can, in its worst form, lead to many researchers torturing the data to come up with a counter-intuitive result just for the novelty factor.

In its best form, of course, this can mean that the papers that make up ‘common wisdom’ are thoroughly scrutinised. And any incorrect assumptions will be challenged, and updated to come up with different (and more accurate) results.

However, at the end of the day, an academic isn’t going to make splashes if they thoroughly scrutinise an existing paper, and confirm the results of that paper.

So this is kinda where we’re at with the inequality war.

Piketty and co’s findings have been thoroughly scrutinised by Auten and Splinter. But the Piketty camp is essentially arguing that Auten and Splinter are incentivised to contradict their findings. How else could they get so much attention?

And as you can see with this line of reasoning, it very quickly moves away from the data and the empirics, and towards ideological factors.

Reason 2: Marketing in academia

Now most researchers will shudder at the thought of ‘marketing’ their work. ‘Marketing’ is a dirty word - sort of like ‘networking’. And when we think of marketing we think of Instagram influencers, Youtubers, etc. However, the incentive structure of academia actually encourages some form of marketing.

The more publicised your research is, the more likely you are to get a book deal or a consulting gig. Book deals and citations are important factors for academic promotions, speaking engagements, and coveted consulting gigs.

Imagine (hypothetically) that you’ve sold the idea that the solution to economic development is better quality institutions, or that the key is all about building industrial clusters. You’re able to capitalise on this research by consulting for governments, development banks, international organisations, and think tanks.

But then someone comes out and provides a data-driven contradiction, finding that these impacts are marginal at best. You’ll defend these ideas to the death because you’re incentivised to. The moment you capitulate and accept defeat is the moment all of these opportunities disappear.

So in essence, part of academia is about creating a brand for yourself. And in certain situations, once you have an established brand, you develop a loyal following—it can become almost cultish. This group of dedicated followers is usually drawn to the bigger ideas you represent, sometimes more than the intricate details of the data.

Once you've established this group of followers, your work starts to take on an ideological tone. The focus shifts from the raw data to the broader narrative your work supports. Your followers are more invested in the ideology you're perceived to represent, rather than the nitty-gritty of your research findings (how many ‘Marxists’ have read Das Kapital?).

This again can mark a shift from data-driven discussion to ideological defence. And this is a reflection of the cycle of academic marketing and influence.

Conclusion

This whole debate is a microcosm for broader issues in academia. It shows us how data-driven research can ultimately descend into ideological bantering.

My hope is that we can move past the whole “inequality denialism” rhetoric, and return to empirical debates over the extent of inequality.

Nonetheless, I want to stress that both parties (Piketty and co; and Auten-Splinter) demonstrate that inequality has worsened — it’s just a question of by what magnitude.

So I hope both parties can also agree that inequality is an important issue and one that deserves more attention.

Sponsor

This newsletter is sponsored by Ekko Graphics, a UK-based design studio that builds websites and geospatial platforms. I’ve worked with them previously at the World Bank, and they’ve built websites and done brand design for two of my former companies, 505 Economics and Lanterne. They’re offering a free consulting call if you’re looking to set up a personal website or develop a geospatial platform.

Thanks - great read, particularly on why this ideological critique can emerge in social 'science'. It might be good to have a prestigious journal dedicate space to articles that do shore up common wisdom! The Auten-Splinter paper seems like a case of incentives working well, though, as you say, and contrary to TP's response.